These tools are wooden handled planes and scrapers with special smaller soles designed for specific purposes. This is a step up from the drawknife and offers more control and can impart a smoother finish. The two handles give the user more control over the direction, shape and depth of the cut. Early nineteenth century handles tend to be larger and with less curves than those of later manufacture, although this is not a hard fast rule. Some early designs have flared oval handles with fine lines.

Spokeshave is a wooden double handled tool with a steel cutter that is used to shape of all things wagon wheel spokes, hence the name. The blade is held into the body with two tangs that pierce the body in square tapered mortices that hold the blade at the correct position by a friction fit. The bevel side of the blade faces up with the flat side on the sole. The body of the spokeshave usually made of beech or other hard dense wood has handles molded on both sides of the narrow thin body that holds the blade. The small sole or face of the spokeshave allows the tool to work on tight inside or outside curves as well as for straight work. The sole of the wooden spokeshave just ahead of the mouth and blade may be equipped with a wear plate. Some come from the manufacturer as brass plates fixed with iron screws. Others are added as the original sole wears out and small pieces of dense material such as bone, ivory, boxwood, lignum vitae or apple wood is dovetailed into the base and can be easily replaced as it wears. Most soles on spokeshaves are flat but some are made with soles that are rounded from front to back to allow working tight inside curves and surfaces.

The cutting depth of the wooden spokeshave is determined by how far the blade is projecting below the base or sole of the spokeshave. The more the blade is projecting the greater the cut. By tapping on the tangs the blade is moved out. Tapping with a wooden mallet on the base of the blade at the tangs decreases the cut of the spokeshave. If the tangs become loose in their mortices small thin hardwood wedges can be made to secure the tangs. They are placed on the end grain side of the mortice to push out in the proper direction to prevent the spokeshave body from splitting.

Not limited to wagon wheel spokes, the spoke shave can be used to shape slats for chairs, rough out work for turning on the lathe or making other spindle work.

Using a spokeshave is like using a small two-handled plane and should be worked with the grain of the wood, as you would do with a low angled hand plane. Working the spokeshave blade at a skew to the grain of the wood will produce a finer cut. On tricky grain changes you can work cross grain to smooth out the work.

You will develop a feel for this tool and in some cases you will use it on the push stroke, which seems to be the more common method of using this tool. You will also find that it can be of help to be able to use the tool on the pull stroke. Your grip on the handles will give you the necessary control to be able to present the blade to the wood at the proper angle. The oval shape to the handles also gives better leverage and control when using this tool.

Metal Spokeshave was introduced in the nineteenth century and used extensively by the coach making and wheel making trades. Its popularity stems from its durability in a hostile shop environment. Coaches are made in the center of the shop on sawhorses and the tools were frequently on the floor among the chips, shavings and sawdust. Stepping on a wooden handled spokeshave could ruin the tool and with the Industrial Revolution in full swing, cast metal spokeshaves were a boon for the coach making trades. The configuration of the metal spokeshave is different from the traditional wooden spokeshave in that the blade is more like a plane blade with the bevel down. Metal screws or thumbscrews hold the blade in place and makes blade adjustment easy. These are available with flat soles or curved soles and a flat blade; others have convex or concave sole and blade for special purpose shaping. This tool never completely replaced wooden spokeshaves as they are completely different tools and work in distinct ways.

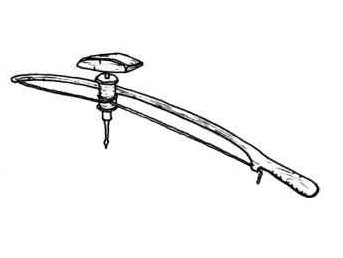

Travisher is a spokeshave with a convex blade and is used for hollowing on seat bottoms, bowls, trenchers and other inside curves. Some of these early examples have beautiful curves to the base and the handles. The configuration of the blade is the same as a wooden spokeshave with the low cutting angle on the blade; the difference is the large sweeping curve of the blade and body. When the tool becomes dull, it tends to chatter and catch in the wood, so keep the blade sharp to make your work easier. This tool is easier to work on the push stroke because your thumbs need to be held down on the body to give you a purchase on the tool and to keep the blade engaged with the wood. If you try and pull the tool towards yourself, the leverage will work against you. It is much easier to work on the push stroke. To clean up the bottom of a cut, the travisher is used across grain to deal with the changing grain direction and using at a skew can also help smooth the grain. There is also a scraper version of this tool that has an almost vertical blade sharpened like a cabinet scraper. It can be used to smooth up after the spokeshave version as brought the work to rough shape.

Buzz is a term for a simple cabinet scraper. A common use of these tools was to smooth down the outside of coopered barrels. These tools can have a flat base but most are concave to handle the curved staves of the barrel. It is used in the direction of the grain of the wood, so the concave sole is from side to side. The staves are worked from the center bulge of the barrel to each end. The blade is sharpened like a cabinet scraper with a bevel ground on one side to a 60 to 70° angle and a burr is turned towards the flat side. The angle of the blade can be at 90° to the sole or it can slat forward 5° or so. The two wedges hold each edge of the scraper blade tight in the body of the buzz. A small piece of leather or veneer is placed behind the blade before it is secured. This will cause the blade to bow out slightly producing a fine cut when properly sharpened and set. It may require a bit of fussing getting the bow just right but then once you get it right it becomes quite easy. If the tool chatters during use, it usually means that the blade is set too proud. When the shavings from this tool turn from clean thin scrapings to powder or dust the tool is dull and requires re-sharpening. Versions with flat soles can be used just as a cabinet scraper; the flat bottom helps keep the scraping flat and smooth. This tool is usually worked by holding with both hands, with the thumbs down on the body of the tool and pushing the tool away from yourself. You can also pull the tool towards yourself but the control may not be as exact as with the push stroke. This tool also cuts well against the grain of the wood, but produces the finest cut when worked in the direction of the grain.

Jarvis is a tool similar to a buzz a cabinet scraper built for a specific purpose. Used to smooth tool handles, spokes and other round cylinders of wood. After a split of wood is roughed out using an ax, drawknife and spokeshave, the Jarvis is used to scrape the wood smooth. If the wood is cut rather than split then attention needs to be paid to the grain direction and as always work with the grain. A split of wood insures that the grain of the wood runs from end to end. On splits of wood, one end will be slightly larger that the other as the tree gets smaller towards the top of the tree. Start at the large end and work towards the smaller end to prevent the tool from digging into the grain. This is more important with cutting tools more than with a scraping tool like a Jarvis. Scrapers will work in both directions of the grain of wood, but with the grain is always smoother. When the fine shavings turn to dust or powder instead of fine thin shavings, the tool is dull and needs to be sharpened.